Coup, Contrecoup

The Conclusion of Trial 1: The Sentencing of Jesse Matthew in the Case of R.G., Fairfax, Virginia

At 4 a.m., on October 2nd, 2015, the hulking form of Jesse Matthew twitched and moaned as he strangled a girl to death.

He grunted a porcine satisfaction so loud that he woke himself, as he lay sprawled on the jail cot.

His cell was dark.

The scene was already disintegrating, but for a few seconds longer, he could see and enjoy himself as he had dreamed, with oily boar hairs erect and askew on the backs of his hands, and stiff steel daggers running like an urban mane along his big spine. His thighs bristled with hard blue thorn-like protuberances. His stance was strange and wide, and he stood on dull black goat's hooves.

This was no costume.

Other girls screamed and fled.

But he commanded a swarm of flies and wasps, who rushed to knit a thick and painful fence.

So all the girls were trapped.

And he would kill them all.

But the halogen round of a punctual prison guard vaporized the last of Jesse Matthew's dream.

He tried to go back to sleep, to re-enter his paradise, unaware that Angels had conferred and chosen this very morning, the day of Jesse's first sentencing, to deliver their own cauterizing sentence.

It wasn't a power they used often.

Only the oldest Angels remembered this ritual, The Cutting of Dreams.

Ancient Angels, as old civilizations did, hold clearer, calmer belief in evil, and more resolve to prevent its play.

Jesse's repetitive sadistic dreams of monstrous defilements so offended the Heavens, the Angels were intervening.

And so, at 4:30 a.m., a troupe of them rode that prison guard's halogen beam like kids on a water slide, and landed in Jesse's unconscious.

They went to work like the shoemaker's elves, tribal Angels in a chiming circle, waving tiny copper scissors, whispering snips and castanet clicks.

They smiled when the last of the cables of Jesse's dream-world fell, disabled.

Having castrated the nightmare factory, the Angels left him quickly.

His smelliness disturbed them, part filthy feet, part billy goat, even after bathing.

He was unaware of the miracle.

Jesse would never again be able to dream like Hieronymus Bosch.

Simultaneously, my alarm sounded.

I turned on the porch lights. Rain typed muddy answers on my flooded sidewalk.

The troubled lilac hula-hooped in the dark wind.

But I brushed my long hair and drank my English Breakfast, seat-belted, and windshield-wiped down the mountain to pick up Gil Harrington.

The rain was bad all the way to Fairfax; Hurricane Joaquin was surfing off the East Coast, deciding whether he'd make landfall.

I don't think I could cared less about driving into a hurricane.

I was so pleased to be driving, a small offering for my friend.

She would be going into the room again with the cloven-footed man.

We arrived in Fairfax hours early, and ordered salads in a quiet restaurant. Our waiter's Isle of Skye eyes read something unusual in our low voices. He asked, "What brings you out, on this rainy day?"

By the time we paid our check, John the waiter was hugging us goodbye. He wears a Help Save the Next Girl bracelet now, and he knows our story, as we know his story, too, about his two dear friends who were murdered.

Just before we left the restaurant, he searched for words: "Meeting you today was very important for me, more important than I can tell you. You've put hope back inside of me. I think you've cured me."

Then we drove to Court.

Under umbrellas, through chilling air, we walked from the parking garage toward the massive Courthouse.

Outside the great double doors to the room within the vast legal catacomb where Judge Schell would soon preside and sentence, the room where we would witness the Judge's conclusions about what consequences fit Jesse Matthew's abduction, dragging, beating, head-banging, stripping, bloodying, raping, and nearly strangling to death R.G.,

reporters gathered around us. They approached not for quotes, but for embraces.

We were flanked also by victims' advocates who would assist us in being seated on the front row.

We had been told the Grahams were attending; we would be seated together.

We were led to the front, nearest the entrance.

At ten minutes before 2:00 p.m., the susserating hive began to gather behind us, baby-stepping closer and closer. We packed as a crowd in an elevator, without the elevator, a civilized block of minds all tuned to hear the doors' bolts' electronic click.

Armed policemen studied our specimen faces.

Jesse Matthew's family and a friend or two entered from a side conference room. They were seven.

There was Debra Carr, Jesse's mother, with whom Gil had shaken hands two days before. Separated by three victims' advocates and a guard, Debra also sat at the front, four people down from me, at the end of the front row.

Jesse Matthew was not yet in the room.

His father, Jesse's sister, his minister-uncle and three other people sat on the second bench, behind Debra Carr.

We had hugged the Grahams when we entered. They were serious and stricken. After we were all seated, I looked to check on the Grahams again, who were seated just past Gil, who sat on my left. I saw Hannah in both John's and Sue's weary faces, but nothing of Hannah's smile.

In the brief and awful silence before the Judge entered, my heart started to pound. Yes, Gil said--because I asked, figuring that if my heart were booming, so would be hers--she was alright. We asked who all the people were, sitting to the far left, in what are usually the jury's seats. They were watching us in the dead girls' row. Young clerks, who have been given the privilege to witness this historic sentencing.

Finally, announced with somber pomp, Judge Schell entered, his face an argument between thundercloud and ice.

Fifteen days shy of six years since Morgan's murder, one year plus nineteen days days since Hannah's murder. Morgan was twenty, Hannah was eighteen. Both college girls dumped in remote spots. Morgan in a high mountain pasture, Hannah in a ravine creek bed, just a few miles apart from one another.

Judge Schell ordered in the abominable goat-man.

Jesse Matthew glanced for one second at his family, and for one second at us. He wore a forest green jumpsuit and had tied back his massive dreadlocks. I wondered if in their thick tangled luxuriance he had tucked some stump or amputation from his ugly morning dream.

Keep your thumb off the nozzle, Gil has said for six years; keep fear and doubt in check; let us do all the good we can do; let us drink from the fire hose; let us not limit the amplitude of the goodness we can do, as we, like accidental crusaders, try, through legislation, education, victims' outreach, social media, campus presence, strong graphics, web, radio, television, and newspaper saturation, and a new paradigm of relationship with law enforcement, let us really try to Help Save the Next Girl.

Absorbing Gil's admiral insights, witnessing Dan and Gil's storybook tears and generosity, a few of us, over these six years, became a million of us.

Judge Schell heard Prosecutor Morrogh review the lurid details of the 2005 near-murder of the young woman, R.G., who had been walking home from having relaxed in a Fairfax book store, carrying milk and vegetables to her apartment. Not from Jesse Matthew's mercy, Morrogh emphasizes, but only because a stranger and hero named Mr. Castro happened upon the scene at exactly the Moment of Salvation with his Angelic headlights--Predator interrupted by Protector--did R.G. barely live through the extreme assault.

Prosecutor Morrogh quoted from Robert Louis Stephenson's Victorian novel about Henry Jekyl and Edward Hyde, the conflation of possibility and doom, of social congeniality by day and vicious murderous child-trampling rage by night, which ends with depravity having unhinged its serpent jaws and utterly swallowing decency.

The Defense had little to say.

Jesse was 24 when he committed the crimes. He has seven people who came to the Courtroom to be with him today. We, the Defense Team (who knew better) think he is a gentle giant. Oh, and his father was an alcoholic who had a lot of affairs.

The defendant should stand, Judge Schell ordered, and Jesse stood and faced Judge Schell.

Behind us, the Courtroom's dozens of reporters, who were allowed to have been typing and tweeting the whole time, had been zipping out every word of the proceedings.

The most fateful words were about to be spoken.

"Jesse Matthew, do you have anything you would like to say to the Court?"

No.

Nothing.

Jesse Matthew had exactly NOTHING to say.

To the man in whose hands lies his tenuous fate, nothing.

To the parents of two murdered girls, nothing.

To his own mother, nothing.

When Judge Schell began to speak, his force and might awed the Courtroom. I remembered religious friends saying, My God is an awesome God. Judge Schell suddenly uncovered an awesome, marvelous, fierce vast sky of clear truth. He was an awesome Judge.

He spoke immediately of the unusual violence, savagery, and cruelty of Jesse's crimes.

And then Judge Schell brought out the first iron railroad tie and smashed it down with one strike:

"For the attempted murder of R.G., you are sentenced to life in prison."

"For the brutal and violent rape of R.G., you are sentenced to life in prison."

Gil and I were leaning into one another. She didn't blink.

I noticed: there, on Gil's wrist, was the silver bracelet that Morgan wore the night she was murdered and dumped in that pasture, October 17th, 2009; the bracelet which held vigil with Morgan's remains for 100 nights, through all of that autumn to the cold scudding January 26th morning when bracelet was recovered from Morgan's skeletonized arm and blackened, molded wrist.

Morgan's stubborn corpse thrown there on the ground in the fallow pasture, on the 101st morning of her being missing, still maintained enough flesh for the forensic labs to test for many things about that night and her murderer.

Debra Carr opened her mouth.

The sounds began as primitive code.

The sounds were little dots and dashes of strange pterodactyl resonance, which grew into piteous visceral keening, and very quickly transformed into frightening howls and banshee screeches and agonized screams at volumes so wild and horrible no one around me heard the Judge pronounce the third life sentence, or that the three life sentences should be served consecutively.

Debra Carr had lost her son.

She was screaming against Hell. And losing.

Hell had claimed Jesse Matthew long ago, and today the claim was final.

"Rot in Hell!," Debra Carr spewed at the Judge. "F--- off!," she screamed at her own daughter, Jesse's sister, who had joined three guards and other family members who were all trying to pull against Debra Carr's superhuman strength.

Her screams were horrible.

The last sounds Jesse Matthew heard as he was handled out of the Courtroom were the agonized, tortured screams of his mother.

"That mother will go home, now," Gil told me later, as we took off our white scarves--R.G.'s favorite color is white; she told me so herself--"and Debra Carr's home will be a death-home. Her son can never come again" (though Debra can visit Jesse, as Dan and Gil and John and Sue can not visit Morgan and Hannah), "but no one will being casseroles and flowers."

It was too bad, Gil noted, that Jesse's mother broke from her deep and genuine sorrow, which everyone could understand, to that deeper core of fury and anger and rage.

Because her fury deafened and burned, no one reported on the beautiful moment that had happened before the sentencing.

Hell loves to obliterate.

Jesse's minister-uncle, a righteous man, had risen from his seat on the row behind us and walked over to put his hands on Gil's and my shoulders. He squeezed gently, nodding as we turned, and made patient, sweet eye contact. "Thank you," he smiled at Gil, and returned to his seat.

Gil's gesture from two days before had been deeply, beautifully received.

She and the Matthew family had now reciprocated compassion, crossing aisles of murder and agony to touch and bless whatever goodness might remain. They had now touched twice.

But a cauldron of Hell had splashed up from the core of Debra Carr and incinerated the goodness. Vitriol and desperation poured forth, a recipe mixing blood and teeth.

Hell, which loves all orifices and openings, poured forth.

With three life sentences stapled to him already, Jesse Matthew now faces two murder trials in Charlottesville, and the death penalty, unless he pleads guilty for the murders of Morgan Harrington and Hannah Graham, and then, only if the Albemarle prosecution team and the Harrington and Graham families are willing to accept his plea, in exchange for taking the death penalty off the table.

Gil has said that Jesse Matthew's guilty plea would be the most humane path for everyone, at this point, including Jesse's family.

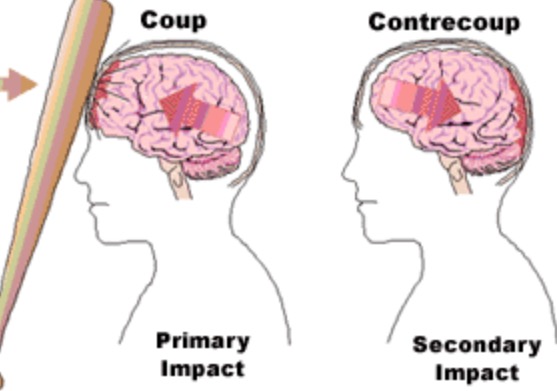

"In nursing school," Gil said on the drive home, this time as she drove, "we learned about coup and contrecoup injuries." The initial injury is, say, a baseball bat hitting a forehead. The brain is injured at the site of impact. But then the second injury, the contrecoup, happens, when the brain is pushed and slams through the meninges and fluid to smash into the back of the skull." The original injury is then injured a third time, exacerbated by the contrecoup injury's volley, since then the brain sloshes yet again from the back of the skull toward the already-contused front."

This increase of injury, the coup, contrecoup karma of grievous injury, is the opposite of the increase of healing and compassion that Gil and Jesse's uncle offered our world.

Unfortunately for Jesse--and the Angels know it--Hell has some escape artists, expert saboteurs, and assassins. Hell's Linebackers can't ever be big King Kongs; those lummoxes are always caught.

Jesse, for instance, could never operate as a big-time, high-status, sexy Hell-being who is selected to go on Earth jobs. He wasn't any good in his 33 free years of sneaking around, killing girls, so Hell has no reason to favor him.

The Hell-artists are subtle; they are insubstantial, creative, and as invisible as Angels.

And these serious pranksters have a mischievous gremlin steak. Right now, they feel affronted and pissed at Jesse for losing his ability even to kill in his dreams.

Whereas he used to be like their big brother, chilling and killing in Charlottesville and beyond, Jesse--he was the host, they, his adoring lice--now has no dreams Hell can suck.

So, now, uh-oh: you guessed it. Coup, contrecoup.

Hell has turned on Jesse.

Not clever enough to have hidden his DNA everywhere he raped and killed; captured and sentenced and harmless now; all tied up like a toothless cartoon crocodile with his big mouth sewn shut, Jesse has pissed off every one of his hellion buddies.

His fan club has folded.

Tonight, they're shaming him.

The skillful little Hell-lice have snuck in through the back door of Jesse's dreams.

They are giggling.

It's 23 hours since Jesse moved around for the last time in a dream, marauding as the snorting, piggish goatish super-villain.

When he wakes in the middle of this night--in one hour--his new enemies will be watching to see his response.

Because they've spent hours, while he has been snoring like a dumb sausage, festooning the rooms at the back of his eyes.

Back there, right now, hanging from the ceiling of his stony brain, Hell has hung welcome streamers, with a nice little party in his mind.

He'll wake to the welcome, and here are the reasons he should know who did the decorating:

The streamers are intestines.

The balloons are kidneys.

The brownies are fingers.

The cake is liver.

"Dear Jesse," a note reads in his mind, taped to the wall at the back of one eye, waiting for him to wake in a few hours and read it, "You are invited to our party. It's really your party. Because, well, all the parts are actually yours.

p.s.

You missed our toying joke, Jesse! You didn't even notice, did you? Dull boy! Get it?

Judge ScHELL.

p.p.s.

See you soon,

See you now,

Said the Butcher

To the Cow.

See you now,

And see you then,

And you will not

Be back again.

Not to home,

And not to kill.

It's your turn, Jesse.

That's the thrill.

Love,

Hell."

Jane Lillian Vance,

Vice President, Help Save the Next Girl, and

Morgan Harrington's professor in the last Spring of her life